Stumbling on Happiness. Daniel Gilbert

Stumbling on Happiness. Daniel GilbertDespite the third word of the title, this is not an instruction manual that will tell you anything useful about how to be happy. Those books are located in the self-help section two aisles over, and once you’ve bought one, done everything it says to do, and found yourself miserable anyway, you can always come back here to understand why. Instead, this is a book that describes what science has to tell us about how and how well the human brain can imagine its own future, and about how and how well it can predict which of those futures it will most enjoy.

This book is about a puzzle that many thinkers have pondered over the last two millennia, and it uses their ideas (and a few of my own) to explain why we seem to know so little about the hearts and minds of the people we are about to become. The story is a bit like a river that crosses borders without benefit of passport because no single science has ever produced a compelling solution to the puzzle. Weaving together facts and theories from psychology, cognitive neuroscience, philosophy, and behavioral economics, this book allows an account to emerge that I personally find convincing but whose merits you will have to judge for yourself.

Contents

- What "Later" means

- Anxiety and planning

- Meditation and not thinking about a future

- About controlling things

- What happiness really is

- Remembering differences

- Perceiving Differences

- Experince stretching

- Dazed and Confused

- Comfortably Numb

- Measuring right

- Realism (what it would feel like if.)

- Filling in Memory

- Filling in Perception

- Discovering Idealism

- Escaping Realism

- An Embarrassment of Tomorrows

- The Hound of Silence

- The Sailors Not

- Absence in the Present

- Absence in the Future

- On the Event Horizon

- Presentism in the Future

- Sneak prefeel

- The Power of Prefeeling

- The Limits of Prefeeling

- Space think

- Starting Now

- Next to Nothing

- Comparing with the Past

- Comparing with the Possible

- Comparing and Presentism

- Paradise Glossed

- Stop annoyhing people

- Disambiguating Objects

- Disambiguating Experience

- Cooking with facts

- Finding Facts

- Challenging Facts

- Immune to Reality

- Looking Forward to Looking Backward

- The Intensity Trigger

- The Inescapability Trigger

- Explaining Away

- The Least Likely of Times

- All’s Well

- The Way We Weren’t

- Super-replicators

- Rejecting the Solution

- Afterword

What "Later" means

Adults love to ask children idiotic questions so that we can chuckle when they give us idiotic answers. One particularly idiotic question we like to ask children is this: “What do you want to be when you grow up?” Small children look appropriately puzzled, worried perhaps that our question implies they are at some risk of growing down. If they answer at all, they generally come up with things like “the candy guy” or “a tree climber.” We chuckle because the odds that the child will ever become the candy guy or a tree climber are vanishingly small, and they are vanishingly small because these are not the sorts of things that most children will want to be once they are old enough to ask idiotic questions themselves. But notice that while these are the wrong answers to our question, they are the right answers to another question, namely, “What do you want to be now?” Small children cannot say what they want to be later because they don’t really understand what later means.

So, like shrewd politicians, they ignore the question they are asked and answer the question they can. Adults do much better, of course. When a thirtyish Manhattanite is asked where she thinks she might retire, she mentions Miami, Phoenix, or some other hotbed of social rest. She may love her gritty urban existence right now, but she can imagine that in a few decades she will value bingo and prompt medical attention more than art museums and squeegee men. Unlike the child who can only think about how things are, the adult is able to think about how things will be. At some point between our high chairs and our rocking chairs, we learn about later.

Anxiety and planning

Now, this pair of observations—that damage to certain parts of the frontal lobe can make people feel calm but that it can also leave them unable to plan—seem to converge on a single conclusion. What is the conceptual tie that binds anxiety and planning? Both, of course, are intimately connected to thinking about the future. We feel anxiety when we anticipate that something bad will happen, and we plan by imagining how our actions will unfold over time. Planning requires that we peer into our futures, and anxiety is one of the reactions we may have when we do.

The fact that damage to the frontal lobe impairs planning and anxiety so uniquely and precisely suggests that the frontal lobe is the critical piece of cerebral machinery that allows normal, modern human adults to project themselves into the future. Without it we are trapped in the moment, unable to imagine tomorrow and hence unworried about what it may bring. As scientists now recognize, the frontal lobe “empowers healthy human adults with the capacity to consider the self’s extended existence throughout time.” As such, people whose frontal lobe is damaged are described by those who study them as being “bound to present stimuli,” or “locked into immediate space and time,” or as displaying a “tendency toward temporal concreteness.” In other words, like candy guys and tree climbers, they live in a world without later.

Meditation and not thinking about a future

In the late 1960s, a Harvard psychology professor took LSD, resigned his appointment (with some encouragement from the administration), went to India, met a guru, and returned to write a popular book called Be Here Now, whose central message was succinctly captured by the injunction of its title. The key to happiness, fulfillment, and enlightenment, the ex-professor argued, was to stop thinking so much about the future.

Now, why would anyone go all the way to India and spend his time, money, and brain cells just to learn how not to think about the future? Because, as anyone who has ever tried to learn meditation knows, not thinking about the future is much more challenging than being a psychology professor. Not to think about the future requires that we convince our frontal lobe not to do what it was designed to do, and like a heart that is told not to beat, it naturally resists this suggestion.

Unlike N.N., most of us do not struggle to think about the future because mental simulations of the future arrive in our consciousness regularly and unbidden, occupying every corner of our mental lives. When people are asked to report how much they think about the past, present, and future, they claim to think about the future the most. When researchers actually count the items that float along in the average person’s stream of consciousness, they find that about 12 percent of our daily thoughts are about the future. In other words, every eight hours of thinking includes an hour of thinking about things that have yet to happen. If you spent one out of every eight hours living in my state you would be required to pay taxes, which is to say that in some very real sense, each of us is a part-time resident of tomorrow.

Studies confirm what you probably suspect: When people daydream about the future, they tend to imagine themselves achieving and succeeding rather than fumbling or failing. Indeed, thinking about the future can be so pleasurable that sometimes we’d rather think about it than get there.

Researchers have discovered that when people find it easy to imagine an event, they overestimate the likelihood that it will actually occur. Because most of us get so much more practice imagining good than bad events, we tend to overestimate the likelihood that good events will actually happen to us, which leads us to be unrealistically optimistic about our futures.

Apparently, three big jolts that one cannot foresee are more painful than twenty big jolts that one can.

About controlling things

The fact is that human beings come into the world with a passion for control, they go out of the world the same way, and research suggests that if they lose their ability to control things at any point between their entrance and their exit, they become unhappy, helpless, hopeless, and depressed.

And occasionally dead. In one study, researchers gave elderly residents of a local nursing home a houseplant. They told half the residents that they were in control of the plant’s care and feeding (high-control group), and they told the remaining residents that a staff person would take responsibility for the plant’s well-being (low-control group). Six months later, 30 percent of the residents in the low-control group had died, compared with only 15 percent of the residents in the high-control group. A follow-up study confirmed the importance of perceived control for the welfare of nursing-home residents but had an unexpected and unfortunate end.

Apparently, gaining control can have a positive impact on one’s health and well-being, but losing control can be worse than never having had any at all.

Our desire to control is so powerful, and the feeling of being in control so rewarding, that people often act as though they can control the uncontrollable. For instance, people bet more money on games of chance when their opponents seem incompetent than competent—as though they believed they could control the random drawing of cards from a deck and thus take advantage of a weak opponent. People feel more certain that they will win a lottery if they can control the number on their ticket, and they feel more confident that they will win a dice toss if they can throw the dice themselves. People will wager more money on dice that have not yet been tossed than on dice that have already been tossed but whose outcome is not yet known,46 and they will bet more if they, rather than someone else, are allowed to decide which number will count as a win.

In each of these instances, people behave in a way that would be utterly absurd if they believed that they had no control over an uncontrollable event. But if somewhere deep down inside they believed that they could exert control—even one smidgen of an iota of control—then their behavior would be perfectly reasonable. And deep down inside, that’s precisely what most of us seem to believe.

Why isn’t it fun to watch a videotape of last night’s football game even when we don’t know who won? Because the fact that the game has already been played precludes the possibility that our cheering will somehow penetrate the television, travel through the cable system, find its way to the stadium, and influence the trajectory of the ball as it hurtles toward the goalposts!

Perhaps the strangest thing about this illusion of control is not that it happens but that it seems to confer many of the psychological benefits of genuine control. In fact, the one group of people who seem generally immune to this illusion are the clinically depressed, who tend to estimate accurately the degree to which they can control events in most situations. These and other findings have led some researchers to conclude that the feeling of control—whether real or illusory—is one of the wellsprings of mental health.

So if the question is “Why should we want to control our futures?” then the surprisingly right answer is that it feels good to do so—period. Impact is rewarding. Mattering makes us happy. The act of steering one’s boat down the river of time is a source of pleasure, regardless of one’s port of call.

We insist on steering our boats because we think we have a pretty good idea of where we should go, but the truth is that much of our steering is in vain—not because the boat won’t respond, and not because we can’t find our destination, but because the future is fundamentally different than it appears through the prospectiscope. Just as we experience illusions of eyesight (“Isn’t it strange how one line looks longer than the other even though it isn’t?”) and illusions of hindsight (“Isn’t it strange how I can’t remember taking out the garbage even though I did?”), so too do we experience illusions of foresight—and all three types of illusion are explained by the same basic principles of human psychology.

What happiness really is

There are thousands of books on happiness, and most of them start by asking what happiness really is. As readers quickly learn, this is approximately equivalent to beginning a pilgrimage by marching directly into the first available tar pit, because happiness really is nothing more or less than a word that we word makers can use to indicate anything we please. The problem is that people seem pleased to use this one word to indicate a host of different things, which has created a tremendous terminological mess on which several fine scholarly careers have been based. If one slops around in this mess long enough, one comes to see that most disagreements about what happiness really is are semantic disagreements about whether the word ought to be used to indicate this or that, rather than scientific or philosophical disagreements about the nature of this and that. What are the this and the that that happiness most often refers to?

The word happiness is used to indicate at least three related things, which we might roughly call emotional happiness, moral happiness, and judgmental happiness.

Emotional happiness

Emotional happiness is the most basic of the trio—so basic, in fact, that we become tongue-tied when we try to define it, as though some bratty child had just challenged us to say what the word the means and in the process made a truly compelling case for corporal punishment. Emotional happiness is a phrase for a feeling, an experience, a subjective state, and thus it has no objective referent in the physical world.

The musician Frank Zappa is reputed to have said that writing about music is like dancing about architecture, and so it is with talking about yellow. If our new drinking buddy lacks the machinery for color vision, then our experience of yellow is one that it will never share—or never know it shares—no matter how well we point and talk.

The dictionary tells us that to prefer is “to choose or want one thing rather than another because it would be more pleasant,” which is to say that the pursuit of happiness is built into the very definition of desire.

Moral happiness (Feeling Happy Because)

If every thinker in every century has recognized that people seek emotional happiness, then how has so much confusion arisen over the meaning of the word? One of the problems is that many people consider the desire for happiness to be a bit like the desire for a bowel movement: something we all have, but not something of which we should be especially proud. The kind of happiness they have in mind is cheap and base—a vacuous state of “bovine contentment” that cannot possibly be the basis of a meaningful human life. As the philosopher John Stuart Mill wrote, “It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied. And if the fool, or the pig, are a different opinion, it is because they only know their own side of the question.”

Judgmental happiness (Feeling Happy About)

The you-know-what-I-mean feeling is what people ordinarily mean by happiness, but it is not the only thing they mean. If philosophers have muddled the moral and emotional meanings of the word happiness, then psychologists have muddled the emotional and judgmental meanings equally well and often. For example, when a person says, “All in all, I’m happy about the way my life has gone,” psychologists are generally willing to grant that the person is happy. The problem is that people sometimes use the word happy to express their beliefs about the merits of things, such as when they say, “I’m happy they caught the little bastard who broke my windshield,” and they say things like this even when they are not feeling anything vaguely resembling pleasure.

Remembering differences

Perhaps the happiness one experiences as a result of good deeds feels different from that other sort.

In fact, while we’re at it, we might as well wonder whether the happiness one gets from eating banana-cream pie feels different from the happiness one gets from eating coconut-cream pie. Or from eating a slice of this banana-cream pie rather than a slice of that one. How can we tell whether subjective emotional experiences are different or the same?

... memories of experiences—are notoriously unreliable, a fact that has been demonstrated by both magicians and scientists.

Only 33 percent of the describers were able to accurately identify the original color. Apparently, the describers’ verbal descriptions of their experiences “overwrote” their memories of the experiences themselves, and they ended up remembering not what they had experienced but what they had said about what they experienced. And what they had said was not clear and precise enough to help them recognize it when they saw it again thirty seconds later.

Perceiving Differences

Our remembrance of things past is imperfect, thus comparing our new happiness with our memory of our old happiness is a risky way to determine whether two subjective experiences are really different.

Amazingly, volunteers did not notice that the text was alternating between different styles several times each second as they read it. Subsequent research has shown that people fail to notice a wide range of these “visual discontinuities,” which is why filmmakers can suddenly change the style of a woman’s dress or the color of a man’s hair from one cut to the next, or cause an item on a table to disappear entirely, all without ever waking the audience.

And it isn’t just the subtle changes we miss. Even dramatic changes to the appearance of a scene are sometimes overlooked. In an experiment taken straight from the pages of Candid Camera, researchers arranged for a researcher to approach pedestrians on a college campus and ask for directions to a particular building. While the pedestrian and the researcher conferred over the researcher’s map, two construction workers, each holding one end of a large door, rudely cut between them, temporarily obstructing the pedestrian’s view of the researcher. As the construction workers passed, the original researcher crouched down behind the door and walked off with the construction workers, while a new researcher, who had been hiding behind the door all along, took his place and picked up the conversation. The original and substitute researchers were of different heights and builds and had noticeably different voices, haircuts, and clothing. You would have no trouble telling them apart if they were standing side by side. So what did the Good Samaritans who had stopped to help a lost tourist make of this switcheroo? Not much. In fact, most of the pedestrians failed to notice—failed to notice that the person to whom they were talking had suddenly been transformed into an entirely new individual.

What’s important to note for our purposes is that card tricks like this work for precisely the same reason that people find it difficult to say how happy they were in their previous marriages.

Studies such as these demonstrate that once we have an experience, we cannot simply set it aside and see the world as we would have seen it had the experience never happened.

- All of this means that when people have new experiences that lead them to claim that their language was squished—that they were not really happy even though they said so and thought so at the time—they can be mistaken.

- In other words, people can be wrong in the present when they say they were wrong in the past.

Experince stretching

Experience stretching is a bizarre phrase but not a bizarre idea. We often say of others who claim to be happy despite circumstances that we believe should preclude it that “they only think they’re happy because they don’t know what they’re missing.” Okay, sure, but that’s the point.

Not knowing what we’re missing can mean that we are truly happy under circumstances that would not allow us to be happy once we have experienced the missing thing.

Dazed and Confused

Rabid wolverines, crying babies, hurled rocks, beckoning mates, cowering prey—these things count for a lot in the game of survival, which requires that we take immediate action when we happen upon them and do not dally to contemplate the finer points of their identities. As such, our brains are designed to decide first whether objects count and to decide later what those objects are. This means that when you turn your head to the left, there is a fraction of a second during which your brain does not know that it is seeing a wolverine but does know that it is seeing something scary.

Comfortably Numb

The distinction between experience and awareness is elusive because most of the time they hang together so nicely.

Our visual experience and our awareness of that experience are generated by different parts of our brains, and as such, certain kinds of brain damage (specifically, lesions to the primary visual cortical receiving area known as V1) can impair one without impairing the other, causing experience and awareness to lose their normally tight grip on each other.

For example, people who suffer from the condition known as blindsight have no awareness of seeing, and will truthfully tell you that they are completely blind. Brain scans lend credence to their claims by revealing diminished activity in the areas normally associated with awareness of visual experience. On the other hand, the same scans reveal relatively normal activity in the areas associated with vision. So if we flash a light on a particular spot on the wall and ask the blindsighted person if she saw the light we just flashed, she tells us, “No, of course not. As you might infer from the presence of the guide dog, I’m blind.” But if we ask her to make a guess about where the light might have appeared—just take a stab at it, say anything, point randomly if you like—she “guesses” correctly far more often than we would expect by chance. She is seeing, if by seeing we mean experiencing the light and acquiring knowledge about its location, but she is blind, if by blind we mean that she is not aware of having seen. Her eyes are projecting the movie of reality on the little theater screen in her head, but the audience is in the lobby getting popcorn.

Measuring right

Even a clock can be a useful device for measuring happiness, because startled people tend to blink more slowly when they are feeling happy than when they are feeling fearful or anxious

Realism (what it would feel like if.)

Fischer and Eastman are a fascinating contrast. Both men believed that common laborers have a right to fair wages and decent working conditions, and both dedicated much of their lives to bringing about social change at the dawn of the industrial age. Fischer failed abysmally and died a criminal, poor and reviled. Eastman succeeded absolutely and died a champion, affluent and venerated. So why did a poor man who had accomplished so little stand happily at the threshold of his own lynching while a rich man who had accomplished so much felt driven to take his own life? Fischer’s and Eastman’s reactions to their respective situations seem so contrary, so completely inverted, that one is tempted to chalk them up to false bravado or mental aberration. Fischer was apparently happy on the last day of a wretched existence, Eastman was apparently unhappy on the last day of a fulfilling life, and we know full well that if we had been standing in either of their places, we would have experienced precisely the opposite emotions. So what was wrong with these guys? I will ask you to consider the possibility that there was nothing wrong with them but that there is something wrong with you. And with me too. And the thing that’s wrong with both of us is that we make a systematic set of errors when we try to imagine “what it would feel like if.”

Imagining “what it would feel like if” sounds like a fluffy bit of daydreaming, but in fact, it is one of the most consequential mental acts we can perform, and we perform it every day.

We make decisions about whom to can perform, and we perform it every day. We make decisions about whom to marry, where to work, when to reproduce, where to retire, and we base these decisions in large measure on our beliefs about how it would feel if this event happened but that one didn’t.

Filling in Memory

the elaborate tapestry of our experience is not stored in memory—at least not in its entirety. Rather, it is compressed for storage by first being reduced to a few critical threads, such as a summary phrase (“Dinner was disappointing”) or a small set of key features (tough steak, corked wine, snotty waiter). Later, when we want to remember our experience, our brains quickly reweave the tapestry by fabricating—not by actually retrieving—the bulk of the information that we experience as a memory.

This fabrication happens so quickly and effortlessly that we have the illusion (as a good magician’s audience always does) that the entire thing was in our heads the entire time.

But it wasn’t, and that fact can be easily demonstrated. For example, volunteers in one study were shown a series of slides depicting a red car as it cruises toward a yield sign, turns right, and then knocks over a pedestrian.5 After seeing the slides, some of the volunteers (the no-question group) were not asked any questions, and the remaining volunteers (the question group) were. The question these volunteers were asked was this: “Did another car pass the red car while it was stopped at the stop sign?” Next, all the volunteers were shown two pictures—one in which the red car was approaching a yield sign and one in which the red car was approaching a stop sign—and were asked to point to the picture they had actually seen. Now, if the volunteers had stored their experience in memory, then they should have pointed to the picture of the car approaching the yield sign, and indeed, more than 90 percent of the volunteers in the no-question group did just that. But 80 percent of the volunteers in the question group pointed to the picture of the car approaching a stop sign.

Clearly, the question changed the volunteers’ memories of their earlier experience, which is precisely what one would expect if their brains were reweaving their experiences—and precisely what one would not expect if their brains were retrieving their experiences.

- First, the act of remembering involves “filling in” details that were not actually stored;

- Second, we generally cannot tell when we are doing this because filling in happens quickly and unconsciously.

For example, read the list of words below, and when you’ve finished, quickly cover the list with your hand. Then I will trick you.

- Bed

- Rest

- Awake

- Tired

- Dream

- Wake

- Snooze

- Blanket

- Doze

- Slumber

- Snore

- Nap

- Peace

- Yawn

- Drowsy

Here’s the trick. Which of the following words was not on the list? Bed, doze, sleep, or gasoline? The right answer is gasoline, of course. But the other right answer is sleep, and if you don’t believe me, then you should lift your hand from the page. (Actually, you should lift your hand from the page in any case, as we really need to move along). If you’re like most people, you knew gasoline was not on the list, but you mistakenly remembered reading the word sleep.

Because all the words on the list are so closely related, your brain stored the gist of what you read (“a bunch of words about sleeping”) rather than storing every one of the words.

Filling in Perception

The eyeball cannot register an image at the point at which the optic nerve attaches, and hence that point is known as the blind spot. No one can see an object that appears in the blind spot because there are no visual receptors there. And yet, if you look out into your living room, you do not notice a black hole in the otherwise smooth picture of your brother-in-law sitting on the sofa, devouring cheese dip. Why? Because your brain uses information from the areas around the blind spot to make a reasonable guess about what the blind spot would see if only it weren’t blind, and then your brain fills in the scene with this information. That’s right, it invents things, creates things, makes stuff up! It doesn’t consult you about this, doesn’t seek your approval. It just makes its best guess about the nature of the missing information and proceeds to fill in the scene

In an even more remarkable study, volunteers listened to a recording of the word eel preceded by a cough (which I’ll denote with ). The volunteers heard the word peel when it was embedded in the sentence “The *eel was on the orange” but they heard the word heel when it was embedded in the sentence “The *eel was on the shoe.” **This is a striking finding because the two sentences differ only in their final word, which means that volunteers’ brains had to wait for the last word of the sentence before they could supply the information that was missing from the second word*.

Discovering Idealism

Without a distinction between things in the world and things in the mind, the child cannot understand how different minds can contain different things. Of course, with increasing maturity, children shift from realism to idealism, coming to realize that perceptions are merely points of view, that what they see is not necessarily what there is, and that two people may thus have different perceptions of or beliefs about the same thing.

Escaping Realism

But if realism goes away, it doesn’t get very far. Research shows that even adults act like realists under certain circumstances. For example, in one study, a pair of adult volunteers were seated on opposite sides of a set of cubbyholes, as shown in figure 9.20 Some common objects were placed in several of the cubbies. Some of these cubbies were open on both sides, so that items such as the large truck and the medium truck were clearly visible to both volunteers. Other cubbies were open on only one side, so that items such as the small truck could be seen by one volunteer but not by the other. The volunteers played a game in which the person with the occluded view (the director) told the person with the clear view (the mover) to move certain objects to certain locations. Now, what should have happened when the director said, “Move the small truck to the bottom row”? If the mover were an idealist, she would move the medium truck because she would realize that the director could not see the small truck, hence he must have been referring to the medium truck, which, from the director’s point of view, was the smallest. On the other hand, if the mover were a realist, then she would move the small truck without regard for the fact that the director could not see it as she could, hence could not have been referring to it when he gave his instruction. So which truck did the movers actually move?

Stumbling on Happiness. Truck experiment

Stumbling on Happiness. Truck experimentThe medium truck, of course. What—did you think they were stupid? These were normal adults. They had intact brains, good jobs, bank accounts, nice table manners—all the usual stuff. They knew that the director had a different point of view and thus must have been talking about the medium truck when he said, “Move the small truck.” But while these normal adults with intact brains behaved like perfect idealists, their hands told only half the story. In addition to measuring the mover’s hand movements, the researchers used an eye tracker to measure the mover’s eye movements as well. The eye tracker revealed that the moment the mover heard the phrase “Move the small truck,” she briefly looked toward the small truck—not the medium truck, which was the smallest truck the director could see, but the small truck, which was the smallest truck that she could see. In other words, the mover’s brain initially interpreted the phrase “the small truck” as a reference to the smallest truck from her own point of view, without regard for the fact that the director’s point of view was different. Only after briefly flirting with the idea of moving the small truck did the mover’s brain consider the fact that the director had a different view and thus must have meant the medium truck, at which point her brain sent her hand instructions to move the proper truck. The hand behaved like an idealist, but the eye revealed that the brain was a momentary realist.

Experiments such as these suggest that we do not outgrow realism so much as we learn to outfox it, and that even as adults our perceptions are characterized by an initial moment of realism.

According to this line of reasoning, we automatically assume that our subjective experience of a thing is a faithful representation of the thing’s properties.

Only later—if we have the time, energy, and ability—do we rapidly repudiate that assumption and consider the possibility that the real world may not actually be as it appears to us. Piaget described realism as “a spontaneous and immediate tendency to confuse the sign and the thing signified“

We believe what we see, and then unbelieve it when we have to.

Because those interpretations are usually so good, because they usually bear such a striking resemblance to the world as it is actually constituted, we do not realize that we are seeing an interpretation

As you are about to see, we sometimes pay a steep price for allowing ourselves to lose sight of this fundamental fact, because the mistake we make when we momentarily ignore the filling-in trick and unthinkingly accept the validity of our memories and our perceptions is precisely the same mistake we make when we imagine our futures.

An Embarrassment of Tomorrows

Research suggests that when people make predictions about their reactions to future events, they tend to neglect the fact that their brains have performed the filling-in trick as an integral part of the act of imagination.

Even though we are aware in some vaguely academic sense that our brains are doing the filling-in trick, we can’t help but expect the future to unfold with the details we imagine. As we are about to see, the details that the brain puts in are not nearly as troubling as the details it leaves out.

The Hound of Silence

By paying careful attention to the absence of an event, Sherlock Holmes further distinguished himself from the rest of humankind. As we are about to see, when the rest of humankind imagines the future, it rarely notices what imagination has missed—and the missing pieces are much more important than we realize.

The Sailors Not

For example, volunteers in one study played a deduction game in which they were shown a set of trigrams (i.e., three-letter combinations such as SXY, GTR, BCG, and EVX). The experimenter then pointed to one of the trigrams and told the volunteers that this trigram was special. The volunteers’ job was to figure out what made the trigram special—that is, to figure out which feature of the special trigram distinguished it from the others. Volunteers saw set after set, and each time the experimenter pointed out the special one. How many sets did volunteers have to see before they deduced the distinctive feature of the special trigram? For half the volunteers, the special trigram was distinguished by the fact that it and only it contained the letter T, and these volunteers needed to see about thirty-four sets of trigrams before they figured out that the presence of T is what made a trigram special. For the other half of the volunteers, the special trigram was always distinguished by the fact that it and only it lacked the letter T. The results were astounding. No matter how many sets of trigrams they saw, none of the volunteers ever figured this out.** It was easy to notice the presence of a letter but, like the barking of a dog, it was impossible to notice its absence.**

Absence in the Present

But studies show that when ordinary people want to know whether two things are causally related, they routinely search for, attend to, consider, and remember information about what did happen and fail to search for, attend to, consider, and remember information about what did not. Apparently, people have been making this mistake for a very long time.

For example, imagine that you are preparing to go on a vacation to one of two islands: Moderacia (which has average weather, average beaches, average hotels, and average nightlife) or Extremia (which has beautiful weather and fantastic beaches but crummy hotels and no nightlife). The time has come to make your reservations, so which one would you choose? Most people pick Extremia. But now imagine that you are already holding tentative reservations for both destinations and the time has come to cancel one of them before they charge your credit card. Which would you cancel? Most people choose to cancel their reservation on Extremia. Why would people both select and reject Extremia?

Because when we are selecting, we consider the positive attributes of our alternatives, and when we are rejecting, we consider the negative attributes.

Extremia has the most positive attributes and the most negative attributes, hence people tend to select it when they are looking for something to select and they reject it when they are looking for something to reject. Of course, the logical way to select a vacation is to consider both the presence and the absence of positive and negative attributes, but that’s not what most of us do.

Absence in the Future

But just as we tend to treat the details of future events that we do imagine as though they were actually going to happen, we have an equally troubling tendency to treat the details of future events that we don’t imagine as though they were not going to happen.

In other words, we fail to consider how much imagination fills in, but we also fail to consider how much it leaves out.

On the Event Horizon

About fifty years ago a Pygmy named Kenge took his first trip out of the dense, tropical forests of Africa and onto the open plains in the company of an anthropologist. Buffalo appeared in the distance—small black specks against a bleached sky—and the Pygmy surveyed them curiously. Finally, he turned to the anthropologist and asked what kind of insects they were. “When I told Kenge that the insects were buffalo, he roared with laughter and told me not to tell such stupid lies.”

The anthropologist wasn’t stupid and he hadn’t lied. Rather, because Kenge had lived his entire life in a dense jungle that offered no views of the horizon, he had failed to learn what most of us take for granted, namely, that things look different when they are far away.

Just as objects that are near to us in space appear to be more detailed than those that are far away, so do events that are near to us in time.

When we think of events in the distant past or distant future we tend to think abstractly about why they happened or will happen, but when we think of events in the near past or near future we tend to think concretely about how they happened or will happen.

Seeing in time is like seeing in space. But there is one important difference between spatial and temporal horizons. When we perceive a distant buffalo, our brains are aware of the fact that the buffalo looks smooth, vague, and lacking in detail because it is far away, and they do not mistakenly conclude that the buffalo itself is smooth and vague. But when we remember or imagine a temporally distant event, our brains seem to overlook the fact that details vanish with temporal distance, and they conclude instead that the distant events actually are as smooth and vague as we are imagining and remembering them. For example, have you ever wondered why you often make commitments that you deeply regret when the moment to fulfill them arrives? We all do this, of course.

When we said yes we were thinking about babysitting in terms of why instead of how, in terms of causes and consequences instead of execution, and we failed to consider the fact that the detail-free babysitting we were imagining would not be the detail-laden babysitting we would ultimately experience.

When volunteers are asked to “imagine a good day,” they imagine a greater variety of events if the good day is tomorrow than if the good day is a year later.

Most of us would pay more to see a Broadway show tonight or to eat an apple pie this afternoon than we would if the same ticket and the same pie were to be delivered to us next month.

Presentism in the Future

... if the present lightly colors our remembered pasts, it thoroughly infuses our imagined futures. More simply said, most of us have a tough time imagining a tomorrow that is terribly different from today, and we find it particularly difficult to imagine that we will ever think, want, or feel differently than we do now.

In one study, researchers challenged some volunteers to answer five geography questions and told them that after they had taken their best guesses they would receive one of two rewards: Either they would learn the correct answers to the questions they had been asked and thus find out whether they had gotten them right or wrong, or they would receive a candy bar but never learn the answers.

Some volunteers chose their reward before they took the geography quiz, and some volunteers chose their reward only after they took the quiz. As you might expect, people preferred the candy bar before taking the quiz, but they preferred the answers after taking the quiz. In other words, taking the quiz made people so curious that they valued the answers more than a scrumptious candy bar. But do people know this will happen? When a new group of volunteers was asked to predict which reward they would choose before and after taking the quiz, these volunteers predicted that they would choose the candy bar in both cases. These volunteers—who had not actually experienced the intense curiosity that taking the quiz produced—simply couldn’t imagine that they would ever forsake a Snickers for a few dull facts about cities and rivers.

Sneak prefeel

As it turns out, the imaginative processes that allow us to discover how a penguin looks even when we are locked in a closet are the same processes that allow us to discover how the future will feel when we are locked in the present.

The moment someone asks you how much you would enjoy finding your partner in bed with the mailman, you feel something. Probably something not so good. Just as you generate a mental image of a penguin and then visually inspect it in order to answer questions about its flippers, so do you generate a mental image of an infidelity and then emotionally react to it in order to answer questions about your future feelings.

The areas of your brain that respond emotionally to real events respond emotionally to imaginary events as well.

Just as imagination previews objects, so does it prefeel events.

The Power of Prefeeling

Prefeeling often allows us to predict our emotions better than logical thinking does.

In one study, researchers offered volunteers a reproduction of an Impressionist painting or a humorous poster of a cartoon cat. Before making their choices, some volunteers were asked to think logically about why they thought they might like or dislike each poster (thinkers), whereas others were encouraged to make their choices quickly and “from the gut” (nonthinkers). Career counselors and financial advisors always tell us that we should think long and hard if we wish to make sound decisions, but when the researchers phoned the volunteers later and asked how much they liked their new objet d’art, the thinkers were the least satisfied.

The Limits of Prefeeling

One of the hallmarks of a visual experience is that we can almost always tell whether it is the product of a real or an imagined object. But not so with emotional experience.

But not so with emotional experience. The emotional experience that results from a flow of information that originates in the world is called feeling; the emotional experience that results from a flow of information that originates in memory is called prefeeling; a**nd mixing them up is one of the world’s most popular sports.**

For example, in one study, researchers telephoned people in different parts of the country and asked them how satisfied they were with their lives. When people who lived in cities that happened to be having nice weather that day imagined their lives, they reported that their lives were relatively happy; but when people who lived in cities that happened to be having bad weather that day imagined their lives, they reported that their lives were relatively unhappy. These people tried to answer the researcher’s question by imagining their lives and then asking themselves how they felt when they did so. Their brains enforced the Reality First policy and insisted on reacting to real weather instead of imaginary lives. But apparently, these people didn’t know their brains were doing this and thus they mistook reality-induced feelings for imagination-induced prefeelings.

Indeed, one of the hallmarks of depression is that when depressed people think about future events, they cannot imagine liking them very much. Vacation? Romance? A night on the town? No thanks, I’ll just sit here in the dark.

We assume that what we feel as we imagine the future is what we’ll feel when we get there, but in fact, what we feel as we imagine the future is often a response to what’s happening in the present.

Space think

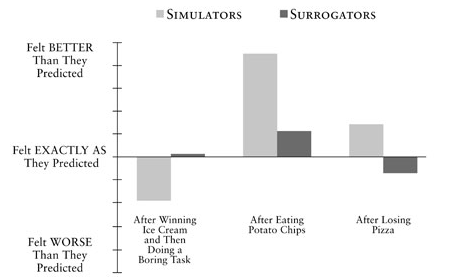

Researchers studied this experience by inviting volunteers to come to the laboratory for a snack once a week for several weeks. They asked some of the volunteers (choosers) to choose all their snacks in advance, and—just as you did—the choosers usually opted for a healthy dose of variety. Next, the researchers asked a new group of volunteers to come to the lab once a week for several weeks. They fed some of these volunteers their favorite snack every time (no-variety group), and they fed other volunteers their favorite snack on most occasions and their second-favorite snack on others (variety group). When they measured the volunteers’ satisfaction over the course of the study, they found that volunteers in the no-variety group were more satisfied than were volunteers in the variety group.

In other words, variety made people less happy, not more.

Wonderful things are especially wonderful the first time they happen, but their wonderfulness wanes with repetition.

The point here is that time and variety are two ways to avoid habituation,

and if you have one, then you don’t need the other. In fact (and this is the really critical point, so please put down your fork and listen), when episodes are sufficiently separated in time, variety is not only unnecessary—it can actually be costly.

Variety increases pleasure when consumption is rapid.

Variety increases pleasure when consumption is rapid. Variety reduces pleasure when consumption is slow.

Variety reduces pleasure when consumption is slow.When dishes are separated by space, it makes perfectly good sense to seek variety. After all, who would want to sit down at a table with twelve identical servings of partridge? We love sampler plates, pupu platters, and all-you-can-eat buffets because we want—and should want—variety among alternatives that we will experience in a single episode. The problem is that when we reason by metaphor and think of a dozen successive meals in a dozen successive months as though they were a dozen dishes arranged on a long table in front of us, we mistakenly treat sequential alternatives as though they were simultaneous alternatives.

This is a mistake because sequential alternatives already have time on their side, hence variety makes them less pleasurable rather than more.

Simultaneous consumption (left) and sequential consumption (right).

Simultaneous consumption (left) and sequential consumption (right).Starting Now

Because time is so difficult to imagine, we sometimes imagine it as a spatial dimension. And sometimes we just don’t imagine it at all.

We can inspect a mental image and see who is doing what and where, but not when they are doing it. In general, mental images are atemporal.

So how do we decide how we will feel about things that are going to happen in the future? The answer is that we tend to imagine how we would feel if those things happened now, and then we make some allowance for the fact that now and later are not exactly the same thing.

Next to Nothing

Indeed, people hate pay cuts, but research suggests that the reason they hate pay cuts has very little to do with the pay part and everything to do with the cut part. For instance, when people are asked whether they would prefer to have a job at which they earned $30,000 the first year, $40,000 the second year, and $50,000 the third year, or a job at which they earned $60,000 then $50,000 then $40,000, they generally prefer the job with the increasing wages, despite the fact that they would earn less money over the course of the three years.

Comparing with the Past

For instance, most of us would be willing to drive across town to save $50 on the purchase of a $100 radio but not on the purchase of a $100,000 automobile because $50 seems like a fortune when we’re buying radios (“Wow, Target has the same radio for half off!”) but a pittance when we’re buying cars (“Like I’m going to schlep across the city just to get this car for one twentieth of a percent less?”).

Economists shake their heads at this kind of behavior and will correctly tell you that your bank account contains absolute dollars and not “percentages off.” If it is worth driving across town to save $50, then it doesn’t matter which item you’re saving it on because when you spend these dollars on gas and groceries, the dollars won’t know where they came from.

But these economic arguments fall on deaf ears because human beings don’t think in absolute dollars.

They think in relative dollars, and fifty is or isn’t a lot of dollars depending on what it is relative to (which is why people who don’t worry about whether their mutual-fund manager is keeping 0.5 or 0.6 percent of their investment will nonetheless spend hours scouring the Sunday paper for a coupon that gives them 40 percent off a tube of toothpaste).

For instance, one ancient ploy involves asking someone to pay an unrealistically large cost (“Would you come to our Save the Bears meeting next Friday and then join us Saturday for a protest march at the zoo?”) before asking them to pay a smaller cost (“Okay then, could you at least contribute five dollars to our organization?”).

Studies show that people are much more likely to agree to pay the small cost after having first contemplated the large one,

in part because doing so makes the small cost seems so . . . er, bearable.

The fact that it is so much easier to remember the past than to generate the possible causes us to make plenty of weird decisions. For instance, people are more likely to purchase a vacation package that has been marked down from $600 to $500 than an identical package that costs $400 but that was on sale the previous day for $300. Because it is easier to compare a vacation package’s price with its former price than with the price of other things one might buy, we end up preferring bad deals that have become decent deals to great deals that were once amazing deals.

We make mistakes when we compare with the past instead of the possible.

Comparing with the Possible

For example, people generally don’t like to buy the most expensive item in a category, hence retailers can improve their sales by stocking a few very expensive items that no one actually buys (“Oh my God, the 1982 Château Haut-Brion Pessac-Léognan sells for five hundred dollars a bottle!”) but that make less expensive items seem like a bargain by comparison (“I’ll just stick with the sixty-dollar zinfandel”).

One of the most insidious things about side-by-side comparison is that it leads us to pay attention to any attribute that distinguishes the possibilities we are comparing.

Because side-by-side comparisons cause me to consider all the attributes on which the cameras differ, I end up considering attributes that I don’t really care about but that just so happen to distinguish one camera from another.

Comparing and Presentism

For instance, economists and psychologists have shown that people expect losing a dollar to have more impact than gaining a dollar, which is why most of us would refuse a bet that gives us an 85 percent chance of doubling our life savings and a 15 percent chance of losing it.

The likely prospect of a big gain just doesn’t compensate for the unlikely prospect of a big loss because we think losses are more powerful than equal-sized gains.

For example, how much is a 1993 Mazda Miata worth? According to my insurance company, the correct answer this year is about $2,000. But as the owner of a 1993 Mazda Miata, I can guarantee that if you wanted to buy my sweet little car with all of its adorable dents and mischievous rattles for a mere $2,000, you’d have to pry the keys out of my cold, dead hands. I also guarantee that if you saw my car, you’d think that for $2,000 I should not only give you the car and the keys but that I should throw in a bicycle, a lawn mower, and a lifetime subscription to The Atlantic. Why would we disagree about the fair value of my car? Because you would be thinking about the transaction as a potential gain (“Compared with how I feel now, how happy will I be if I get this car?”) and I would be thinking about it as a potential loss (“Compared with how I feel now, how happy will I be if I lose this car?”).

Paradise Glossed

The fact is that negative events do affect us, but they generally don’t affect us as much or for as long as we expect them to.

When people are asked to predict how they’ll feel if they lose a job or a romantic partner, if their candidate loses an important election or their team loses an important game, if they flub an interview, flunk an exam, or fail a contest, they consistently overestimate how awful they’ll feel and how long they’ll feel awful.

Able-bodied people are willing to pay far more to avoid becoming disabled than disabled people are willing to pay to become able-bodied again because able-bodied people underestimate how happy disabled people are.

Stop annoyhing people

By carefully measuring what an organism did when it was presented with a physical stimulus, such as a light, a sound, or a piece of food, psychologists hoped to develop a science that linked observable stimuli to observable behavior without using vague and squishy concepts such as meaning to connect them. Alas, this simpleminded project was doomed from the start, because

while rats and pigeons may respond to stimuli as they are presented in the world, people respond to stimuli as they are represented in the mind.

Objective stimuli in the world create subjective stimuli in the mind, and it is these subjective stimuli to which people react.

Disambiguating Objects

For example, why is it that you think of yourself as a talented person? (C’mon, give it up. You know you do.) To answer this question, researchers asked some volunteers (definers) to write down their definition of talented and then to estimate their talent using that definition as a guide.

Next, some other volunteers (nondefiners) were given the definitions that the first group had written down and were asked to estimate their own talent using those definitions as a guide. Interestingly, the definers rated themselves as more talented than the nondefiners did. Because definers were given the liberty to define the word talented any way they wished, they defined it exactly the way they wished—namely, in terms of some activity at which they just so happened to excel.

One of the reasons why most of us think of ourselves as talented, friendly, wise, and fair-minded is that these words are the lexical equivalents of a Necker cube, and the human mind naturally exploits each word’s ambiguity for its own gratification.

If you stare at a Necker cube, it will appear to shift its orientation.

If you stare at a Necker cube, it will appear to shift its orientation.Disambiguating Experience

Because experiences are inherently ambiguous, finding a “positive view” of an experience is often as simple as finding the “below-you view” of a Necker cube, and research shows that most people do this well and often.

Consumers evaluate kitchen appliances more positively after they buy them, job seekers evaluate jobs more positively after they accept them, and high school students evaluate colleges more positively after they get into them. Racetrack gamblers evaluate their horses more positively when they are leaving the betting window than when they are approaching it, and voters evaluate their candidates more positively when they are exiting the voting booth than when they are entering it.

A toaster, a firm, a university, a horse, and a senator are all just fine and dandy, but when they become our toaster, firm, university, horse, and senator they are instantly finer and dandier.

Cooking with facts

having a psychological immune system that defends the mind against unhappiness in much the same way that the physical immune system defends the body against illness.

That’s why people seek opportunities to think about themselves in positive ways but routinely reject opportunities to think about themselves in unrealistically positive ways.

Finding Facts

If views are acceptable only when they are credible, and if they are credible only when they are based on facts, then how do we achieve positive views of ourselves and our experience? How do we manage to think of ourselves as great drivers, talented lovers, and brilliant chefs when the facts of our lives include a pathetic parade of dented cars, disappointed partners, and deflated soufflés? The answer is simple:

We cook the facts. There are many different techniques for collecting, interpreting, and analyzing facts, and different techniques often lead to different conclusions,

Good scientists deal with this complication by choosing the techniques they consider most appropriate and then accepting the conclusions that these techniques produce, regardless of what those conclusions might be. But bad scientists take advantage of this complication by choosing techniques that are especially likely to produce the conclusions they favor, thus allowing them to reach favored conclusions by way of supportive facts.

Consider, for instance, the problem of sampling. For example, when volunteers in one study were told that they’d scored poorly on an intelligence test and were then given an opportunity to peruse newspaper articles about IQ tests, they spent more time reading articles that questioned the validity of such tests than articles that sanctioned them.

On the contrary, we spend countless hours and countless dollars carefully arranging our lives to ensure that we are surrounded by people who like us, and people who are like us.

It isn’t surprising, then, that when we turn to the folks we know for advice and opinions, they tend to confirm our favored conclusions—either because they share them or because they don’t want to hurt our feelings by telling us otherwise.

This tendency to seek information about those who have done more poorly than we have is especially pronounced when the stakes are high.

People with life-threatening illnesses such as cancer are particularly likely to compare themselves with those who are in worse shape.

The bottom line is this: The brain and the eye may have a contractual relationship in which the brain has agreed to believe what the eye sees, but in return the eye has agreed to look for what the brain wants.

Challenging Facts

Whether by choosing information or informants, our ability to cook the facts that we encounter helps us establish views that are both positive and credible.

When Democrats and Republicans see the same presidential debate on television, both sets of viewers claim that the facts clearly show that their candidate was the winner. When pro-Israeli and pro-Arab viewers see identical samples of Middle East news coverage, both proponents claim that the facts clearly show that the press was biased against their side.

Volunteers in one study were asked to evaluate the intelligence of another person, and they required considerable evidence before they were willing to conclude that the person was truly smart. But interestingly, they required much more evidence when the person was an unbearable pain in the ass than when the person was funny, kind, and friendly.

When we want to believe that someone is smart, then a single letter of recommendation may suffice; but when we don’t want to believe that person is smart, we may demand a thick manila folder full of transcripts, tests, and testimony.

Apparently it doesn’t take much to convince us that we are smart and healthy, but it takes a whole lotta facts to convince us of the opposite.

Immune to Reality

Wilhelm von Osten was a retired schoolteacher who in 1891 claimed that his stallion, whom he called Clever Hans, could answer questions about current events, mathematics, and a host of other topics by tapping the ground with his foreleg. For instance, when Osten would ask Clever Hans to add three and five, the horse would wait until his master had finished asking the question, tap eight times, then stop. Sometimes, instead of asking a question, Osten would write it on a card and hold it up for Clever Hans to read, and the horse seemed to understand written language every bit as well as it understood speech. Clever Hans didn’t get every question right, of course, but he did much better than anyone else with hooves, and his public performances were so impressive that he soon became the toast of Berlin. But in 1904 the director of the Berlin Psychological Institute sent his student, Oskar Pfungst, to look into the matter more carefully, and Pfungst noticed that Clever Hans was much more likely to give the wrong answer when Osten was standing in back of the horse than in front of it, or when Osten himself did not know the answer to the question the horse had been asked. In a series of experiments, Clever Pfungst was able to show that Clever Hans could indeed read—but that what he could read was Osten’s body language. When Osten bent slightly, Clever Hans would start tapping, and when Osten straightened up, or tilted his head a bit, or faintly raised an eyebrow, Clever Hans would stop. In other words, Osten was signaling Clever Hans to start and stop tapping at just the right moments to create the illusion of horse sense.

Clever Hans was no genius, but Osten was no fraud. Indeed, he’d spent years patiently talking to his horse about mathematics and world affairs, and he was genuinely shocked and dismayed to learn that he had been fooling himself, as well as everyone else. The deception was elaborate and effective, but it was perpetrated unconsciously, and in this Osten was not unique.

On the contrary, research suggests that people are typically unaware of the reasons why they are doing what they are doing, but when asked for a reason, they readily supply one.

When the word hostile is flashed, volunteers judge others negatively. When the word elderly is flashed, volunteers walk slowly. When the word stupid is flashed, volunteers perform poorly on tests.

Volunteers in one study listened to Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. Some were told to listen to the music, and others were told to listen to the music while consciously trying to be happy. At the end of the interlude, the volunteers who had tried to be happy were in a worse mood than were the volunteers who had simply listened to the music. Why? Two reasons.

First, we may be able deliberately to generate positive views of our own experiences if we close our eyes, sit very still, and do nothing else, but research suggests that if we become even slightly distracted, these deliberate attempts tend to backfire and we end up feeling worse than we did before.

Looking Forward to Looking Backward

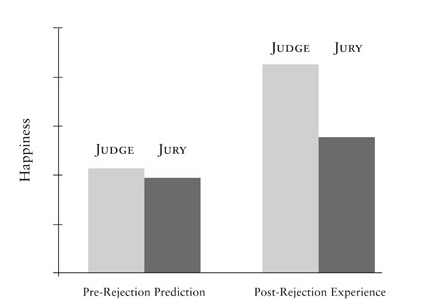

It’s easy to blame failure on the eccentricities of a judge, but it’s much more difficult to blame failure on the eccentricities of a unanimous jury.

Volunteers were happier when they were rejected by a capricious judge than by a unanimous jury (bars on right). But they could not foresee this moments before it happened (bars on left).

Volunteers were happier when they were rejected by a capricious judge than by a unanimous jury (bars on right). But they could not foresee this moments before it happened (bars on left).Being rejected by a large and diverse group of people is a demoralizing experience because it is so thoroughly unambiguous, and hence it is difficult for the psychological immune system to find a way to think about it that is both positive and credible.

For example, people expect to feel equally bad when a tragic accident is the result of human negligence as when it is the result of dumb luck, but they actually feel worse when luck is dumb and no one is blameworthy.

For instance, we expect to feel more regret: - when we learn about alternatives to our choices than when we don’t, - when we accept bad advice than when we reject good advice, - when our bad choices are unusual rather than conventional, and - when we fail by a narrow margin rather than by a wide margin.

You own shares in Company A. During the past year you considered switching to stock in Company B but decided against it. You now find that you would have been better off by $1,200 if you had switched to the stock of Company B. You also owned shares in Company C. During the past year you switched to stock in Company D. You now find out that you’d have been better off by $1,200 if you kept your stock in Company C. Which error causes you more regret? Studies show that about nine out of ten people expect to feel more regret when they foolishly switch stocks than when they foolishly fail to switch stocks,

because most people think they will regret foolish actions more than foolish inactions.

But studies also show that nine out of ten people are wrong. Indeed, in the long run, people of every age and in every walk of life seem to

regret not having done things much more than they regret things they did,

which is why the most popular regrets include not going to college, not grasping profitable business opportunities, and not spending enough time with family and friends.

The Intensity Trigger

The paradoxical consequence of this fact is that it is sometimes more difficult to achieve a positive view of a bad experience than of a very bad experience.

For example, volunteers in one study were students who were invited to join an extracurricular club whose initiation ritual required that they receive three electric shocks.22 Some of the volunteers had a truly dreadful experience because the shocks they received were quite severe (severe-initiation group), and others had a slightly unpleasant experience because the shocks they received were relatively mild (mild-initiation group). Although you might expect people to dislike anything associated with physical pain, the volunteers in the severe-initiation group actually liked the club more.

Because these volunteers suffered greatly, the intensity of their suffering triggered their defensive systems, which immediately began working to help them achieve a credible and positive view of their experience.

Indeed, research shows that when people are given electric shocks,

they actually feel less pain when they believe they are suffering for something of great value

The Inescapability Trigger

For example, college students in one study signed up for a course in black-and-white photography.28 Each student took a dozen photographs of people and places that were personally meaningful, then reported for a private lesson. In these lessons, the teacher spent an hour or two showing students how to print their two best photographs. When the prints were dry and ready, the teacher said that the student could keep one of the photographs but that the other would be kept on file as an example of student work. Some students (inescapable group) were told that once they had chosen a photograph to take home, they would not be allowed to change their minds. Other students (escapable group) were told that once they had chosen a photograph to take home, they would have several days to change their minds—and if they did, the teacher would gladly swap the photograph they’d taken home for the one they’d left behind. Students made their choices and took one of their photographs home. Several days later, the students responded to a survey asking them (among other things) how much they liked their photographs.

The results showed that students in the escapable group liked their photograph less than did students in the inescapable group.

Interestingly, when a new group of students was asked to predict how much they would like their photographs if they were or were not given the opportunity to change their minds, these students predicted that escapability would have no influence whatsoever on their satisfaction with the photograph.

Apparently, inescapable circumstances trigger the psychological defenses that enable us to achieve positive views of those circumstances, but we do not anticipate that this will happen.

Indeed, when our freedom to make up our minds—or to change our minds once we’ve made them up—is threatened, we experience a strong impulse to reassert it, which is why retailers sometimes threaten your freedom to own their products with claims such as “Limited stock” or “You must order by midnight tonight.”

Our fetish for freedom leads us to patronize expensive department stores that allow us to return merchandise rather than attend auctions that don’t, to lease cars at a dramatic markup rather than buying them at a bargain, and so on.

Most of us will pay a premium today for the opportunity to change our minds tomorrow, and sometimes it makes sense to do so.

Explaining Away

Although real students in both groups were initially delighted to have been chosen as everyone’s best friend, only the real students in the uninformed group remained delighted fifteen minutes later. If you’ve ever had a secret admirer, then you understand why real students in the uninformed group remained on cloud nine while real students in the informed group quickly descended to clouds two through five.

Unexplained events seem rare, and rare events naturally have a greater emotional impact than common events do.

The second reason why unexplained events have a disproportionate emotional impact is that we are especially likely to keep thinking about them. People spontaneously try to explain events, and studies show that when people do not complete the things they set out to do, they are especially likely to think about and remember their unfinished business.

but if an event defies explanation, it becomes a* mystery* or a conundrum—and if there’s one thing we all know about mysterious conundrums, it is that they generally refuse to stay in the back of our minds. Filmmakers and novelists often capitalize on this fact by fitting their narratives with mysterious endings, and research shows that people are, in fact, more likely to keep thinking about a movie when they can’t explain what happened to the main character. And if they liked the movie, this morsel of mystery causes them to remain happy longer.

Uncertainty can preserve and prolong our happiness, thus we might expect people to cherish it. In fact, the opposite is generally the case.

We are more likely to generate a positive and credible view of an action than an inaction, of a painful experience than of an annoying experience, of an unpleasant situation that we cannot escape than of one we can. And yet,

we rarely choose action over inaction, pain over annoyance, and commitment over freedom.

The Least Likely of Times

We try to repeat those experiences that we remember with pleasure and pride, and we try to avoid repeating those that we remember with embarrassment and regret. The trouble is that we often don’t remember them correctly.

Are there more four-letter words in the English language that begin with k (k-1’s) or that have k as their third letter (k-3’s)? It is indeed easier to recall k-1’s than k-3’s, but not because you have encountered more of the former than the latter. Rather, it’s easier to recall words that start with k because it is easier to recall any word by its first letter than by its third letter.

The fact is that there are many more k-3’s than k-1’s in the English language, but because the latter are easier to recall, people routinely get this question wrong.

In fact, infrequent or unusual experiences are often among the most memorable, which is why most Americans know precisely where they were on the morning of September 11, 2001, but not on the morning of September 10.

But because we don’t recognize the real reasons why these memories come quickly to mind, we mistakenly conclude that they are more common than they actually are.

This tendency to recall and rely on unusual instances is one of the reasons why we so often repeat mistakes.

Whether we hear a series of sounds, read a series of letters, see a series of pictures, smell a series of odors, or meet a series of people,** we show a pronounced tendency to recall the items at the end of the series far better than the items at the beginning or in the middle**.

As such, when we look back on the entire series, our impression is strongly influenced by its final items.

All’s Well

Memory’s fetish for endings explains why women often remember childbirth as less painful than it actually was.

For example, when the researchers who performed the cold-water study asked the volunteers which of the two trials they would prefer to repeat, 69 percent of the volunteers chose to repeat the long one—that is, the one that entailed an extra thirty seconds of pain.

If we can spend hours enjoying the memory of an experience that lasted just a few seconds, and if memories tend to overemphasize endings, then why not endure a little extra pain in order to have a memory that is a little less painful?

Apparently, the way an experience ends is more important to us than the total amount of pleasure we receive—until we think about it.

Consider, for example, a study in which volunteers learned about a woman (whom we’ll call Ms. Dash) who had an utterly fabulous life until she was sixty years old, at which point her life went from utterly fabulous to merely satisfactory. Then, at the age of sixty-five, Ms. Dash was killed in an auto accident. How good was her life (which is depicted by the dashed line in figure below? On a nine-point scale, volunteers said that Ms. Dash’s life was a 5.7. A second group of volunteers learned about a woman (whom we’ll call Ms. Solid) who had an utterly fabulous life until she was killed in an auto accident at the age of sixty. How good was her life (which is depicted by the solid line in figure below? Volunteers said that Ms. Solid’s life was a 6.5. It appears, then, that these volunteers preferred a fabulous life (Ms. Solid’s) to an equally fabulous life with a few additional merely satisfactory years (Ms. Dash’s). If you think about it for a moment, you’ll realize that this is just how the volunteers in the ice-water study were thinking. Ms. Dash’s life had more “total pleasure” than did Ms. Solid’s, Ms. Solid’s life had a better ending than Ms. Dash’s, and the volunteers were clearly more concerned with the quality of a life’s ending than with the total quantity of pleasure the life contained. But wait a minute. When a third group of volunteers was asked to compare the two lives side by side (as you can do at the bottom of figure below, they showed no such preference. When the difference in the quantity of the two lives was made salient by asking volunteers to consider them simultaneously, the volunteers were no longer so sure that they preferred to live fast, die young, and leave a happy corpse.

Apparently, the way an experience ends is more important to us than the total amount of pleasure we receive—until we think about it.

When considered separately, the shapes of the curves matter. But when directly compared, the lengths of the curves matter.

When considered separately, the shapes of the curves matter. But when directly compared, the lengths of the curves matter.The Way We Weren’t

Our brains use facts and theories to make guesses about past events, and so too do they use facts and theories to make guesses about past feelings.

The point is that these beliefs are theories that can influence how we remember our own emotions.

For instance, Asian culture does not emphasize the importance of personal happiness as much as European culture does, and thus Asian Americans believe that they are generally less happy than their European American counterparts.

These reports showed that the Asian American volunteers were slightly happier than the European American volunteers. But when the volunteers were asked to remember how they had felt that week, the Asian American volunteers reported that they had felt less happy and not more.

... research shows that when students do well on an exam, they remember feeling more anxious before the exam than they actually felt, and when students do poorly on an exam, they remember feeling less anxious before the exam than they actually felt.

We remember feeling as we believe we must have felt.